There is a myth about the United States that people all over the world believe. Many Americans believe it too. And so did Udoh Nkanta, when he first arrived from Nigeria 20 years ago.

“When I first came here, I used to think that everybody speaks English and everybody can read and write,” says Udoh. “But then I found out that people were having the same issue as me. Some people are still struggling to read and write.”

In Nigeria, Udoh had graduated from high school, and his parents had emphasized education since he was a little boy. But when he came to the U.S., he couldn’t read or write English, and most people couldn’t understand him. His accent was too thick.

“People who can’t read and write, it’s very hard for them,” says Udoh. “You beat yourself up all the time, asking ‘Why, why, why?’”

Without knowing how to read, Udoh couldn’t order off a menu, navigate by street signs, browse online or help his kids with their homework. In job interviews, potential employers couldn’t understand his answers. And when he did get jobs—low-wage positions in retail and fast food—customers shook their heads with incomprehension.

Udoh knew he had to do something. When he first heard about the Adult Literacy Center (ALC)—funded by United Way of Central Iowa—at Drake University, he wasn’t sure if he would get anything out of it. But he went anyway.

“Udoh is one of the most positive individuals I have ever encountered,” says Anne Murr, coordinator of the ALC, which teaches adults to read, write and comprehend.

Two-thirds of ALC students lack the very basic skills of reading. One-third are English Language Learners.

Udoh fell into both camps when he first started at the ALC. He credits the intensive one-on-one instruction with teaching him to read, write, spell and pronounce English words better.

Udoh studied at the ALC for more than five years. For much of the time, he was either unemployed or working low-wage jobs while raising two kids as a single dad. But Anne says he always had a huge smile on his face, even after months of using the computers there to apply for jobs without success.

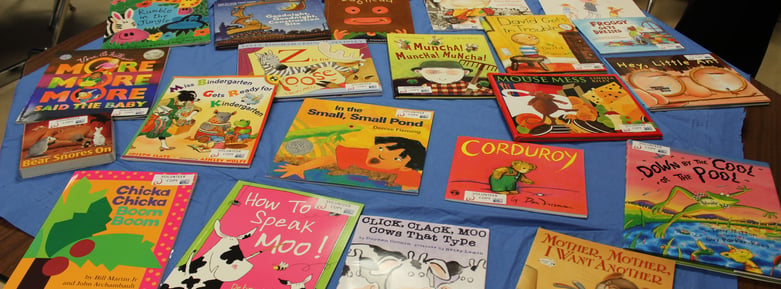

As his reading improved, so did Udoh’s confidence. One day, his tutor asked him to read two pages of a children’s storybook. He read through the sentences smoothly.

“It felt good,” Udoh says. “It was like I won the lottery. In that moment, I knew that I could do it.”

With more practice, Udoh was able to read and speak English proficiently. Although he still has an accent, he’s easy to understand. He can go online, browse Facebook, read news stories, text his children—seemingly small daily routines that we all take for granted. But not Udoh.

“I got something that money can’t buy,” he says. “It’s with me forever. And I can take it anywhere.”

Udoh has taken his hard-earned literacy skills to UTC Aerospace Systems, where he has worked for two years in a high-tech industry. He volunteers in the community and dreams of someday owning his own business. Anne marvels at the change in him. “Look at his competence and his ability to maneuver in a world of words,” she says.

Udoh gives the credit to the ALC, saying he wouldn’t have gotten his current job without their help and calling Anne “his angel.” Anne believes his success is due to his work ethic and dedication to providing for his family. They’re likely both right.

“I feel like I can rule the whole world,” Udoh says with a laugh.

But he gets serious when he talks about the illiteracy problem in the United States, the hidden issue he only recognized when he saw others like himself. “Right now, we have a lot of kids who drop out of school because they can’t read or write,” he says. He encourages them to ask for help. “As long as you put your mind to it and your feet on it, you can get through it. You can do anything you want to.”

Udoh knows, however, that the onus to act isn’t just on those who need help. It’s also on those who can give it. “You don’t have to wait until somebody tells you to volunteer,” he says. “Reach out to somebody. It will make a lot of difference.”

Udoh saves his strongest advice for his children—a son in middle school and a daughter at the University of Northern Iowa. They’ve obviously absorbed his message about reading, but he still keeps at it.

“I tell them every day,” he says. “It’s like I am singing into their ears. They say, ‘Dad, you sing too much.’ I say, ‘That is my song: Education is key. Get an education, and you don’t have to worry. You will be all right.’”

CTA Headline Goes Here Lorem Ipsum Dolor Sit Amet

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur. Quis congue varius a.